Meta-analytic Examination of a Suppressor Effect on Subjective Well-Being and Job Performance Relationship

[Estudio metaanalĂtico de un efecto supresor en la relaciĂłn entre el bienestar subjetivo y el desempeño en el trabajo]

Silvia Moscoso and Jesús F. Salgado

University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a13

Received 28 April 2021, Accepted 10 May 2021

Abstract

This paper presents a meta-analytic study of the relationship between overall subjective well-being (SWB), cognitive SWB, affective SWB, and job performance ratings. The study examined the moderator effect of the source of job performance measure (self-report vs. supervisory ratings). The database consists of 34 independent samples (n = 5,352) using supervisory performance ratings and 38 independent samples (n = 12,086) using self-reported of job performance. These samples were located through electronic and manual searches. The results indicated that, on average, the correlation for SWB- supervisory ratings (ρ = .35) was slightly larger than for SWB-self-reported performance (ρ = .33). The correlation of affective SWB was much higher with supervisory ratings (ρ = .49) than with self-reported performance (ρ = .30). A suppressor effect of cognitive SWB was found for the prediction of supervisory ratings. Finally, we discuss the implications for the theory and the practice of SWB at work and suggest new research avenues.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta un estudio metaanalítico de la relación entre el bienestar subjetivo general (SWB), el SWB cognitivo, el SWB afectivo y las valoraciones de desempeño en el trabajo. El estudio examinó el efecto moderador de la fuente de valoración del desempeño en el trabajo (autoinforme frente a calificaciones de los supervisores). La base de datos consta de 34 muestras independientes (n = 5,352) en las que utilizaron evaluaciones del desempeño realizadas por los supervisores y 38 muestras independientes (n = 12,086) en las que utilizaron autoinformes de desempeño en el trabajo. Las muestras se localizaron mediante búsquedas electrónicas y manuales. Los resultados indicaron que, de promedio, la correlación entre SWB general y las valoraciones de los supervisores (ρ = .35) fue ligeramente mayor que la correlación entre el SWB y los autoinformes de desempeño (ρ = .33). La correlación del SWB afectivo fue mucho mayor con las evaluaciones de los supervisores (ρ = .49) que con los autoinforme de desempeño (ρ = .30). También se encontró un efecto supresor del SWB cognitivo para la predicción de las evaluaciones del desempeño realizadas por los supervisores. Por último, se presentan las implicaciones de los resultados para la teoría y la práctica del SWB en el trabajo y se sugieren nuevas vías de investigación.

Palabras clave

Bienestar subjetivo general, Bienestar afectivo, Bienestar cognitivo, Desempeño en el trabajo, Satisfacción con la vida, Efecto supresorKeywords

Subjective well-being, Affective well-being, Cognitive well-being, Job performance, Satisfaction with life, Suppressor effectCite this article as: Moscoso, S. & Salgado, J. F. (2021). Meta-analytic Examination of a Suppressor Effect on Subjective Well-Being and Job Performance Relationship. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 119 - 131. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a13

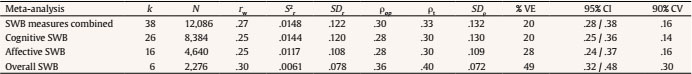

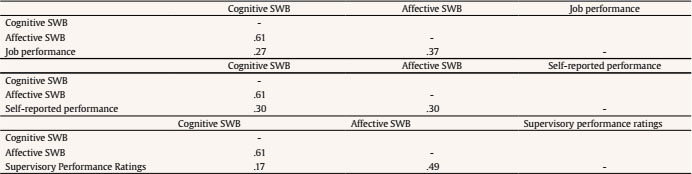

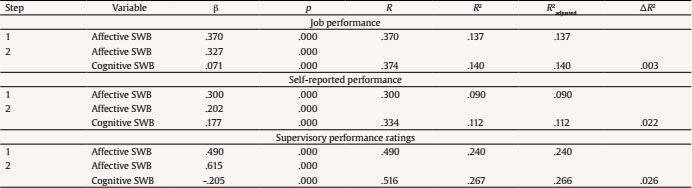

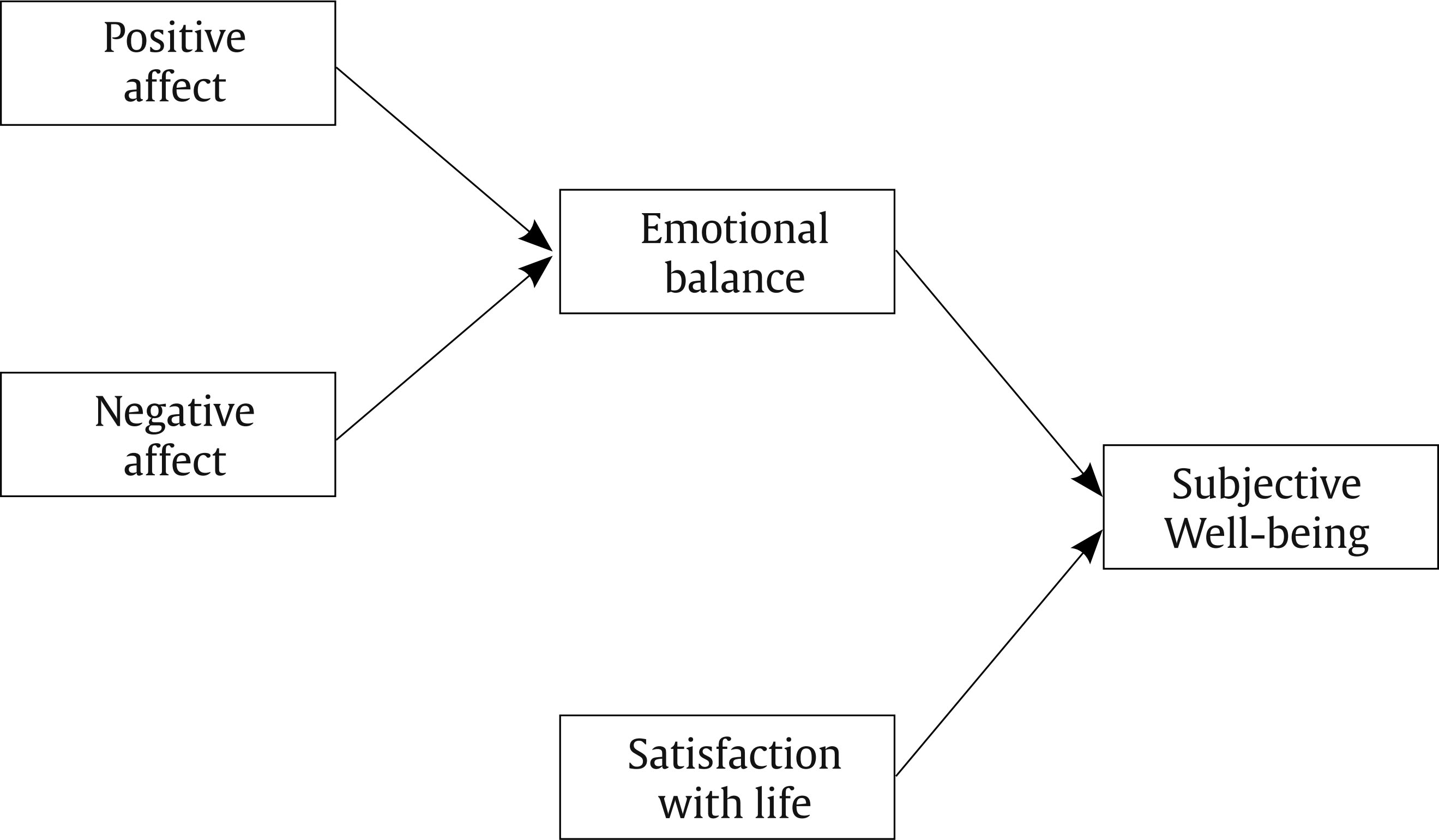

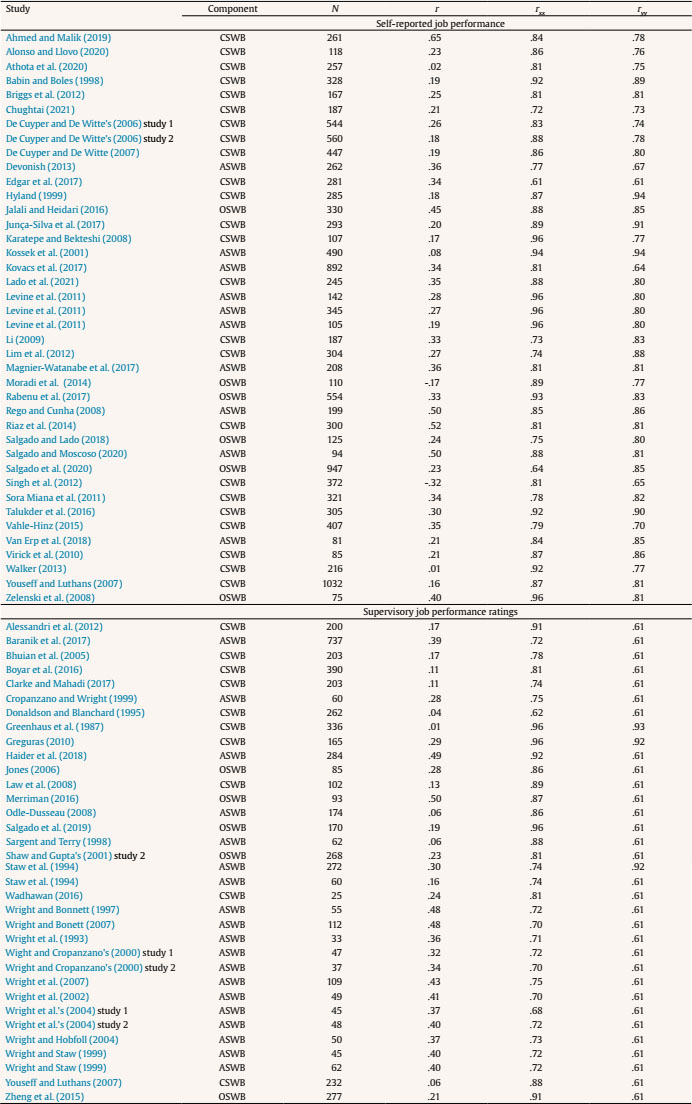

silvia.moscoso@usc.es Correspondence: silvia.moscoso@usc.es (S. Moscoso).Subjective well-being (SWB) refers to the cognitive evaluation and emotional balance that people make of their lives (Diener, 1984, 2000; Diener et al., 2003). Currently, the most widely accepted model of SWB (i.e., Diener’s model) consists of three elements (Busseri, 2015, 2018; Busseri & Sadava, 2011; Tov, 2018): life satisfaction (LS), positive affect (PA), and negative affect (NA). Life satifaction is the SWB cognitive component and it refers to the judgments of life satisfaction. PA and NA are the two elements of the SWB affective component, which refers to the emotional balance (EB) between the level of PA and NA experienced by the individual (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008; Diener et al., 2009). Therefore, a high level of SWB is an effect of the combination of both a high EB and a high LS. Figure 1 represents Diener et al.’s approach to SWB. The relationships among the three elements of Diener’s SWB model are moderately high. For instance, Busseri’s (2018) meta-analysis reported that LS correlated .53 with PA and -.37 with NA. Despite this, Diener et al. (2003) suggested that LS and EB should be independently assessed because they have theoretical and substantive implications. For instance, Diener et al. (2010) found that LS correlated .33 and .30 with income and possession of modern conveniences, respectively. However, EB correlated .14 and .13 with these two variables. On the other hand, EB correlated .32 with the choice of how to spend time, while LS correlated .15 with this variable. Subjective Well-being and Job Performance Research carried out over three decades studied the relationship between SWB and job performance. For example, in a series of pioneer studies, Wright and his colleagues examined the relationship between the affective component of SWB and job performance (Wright & Bonnet, 2007; Wright et al., 1993; Wright & Cropanzano, 2000; Wright et al., 2002; Wright et al., 2007; Wright & Staw, 1999). These researchers found correlations ranging from .23 to .48. Some studies showed even higher correlations (e.g., Ahmed & Malik, 2019; Haider et al., 2018; Merriman, 2016; Odle-Dusseau, 2008; Rego & Cunha, 2008; Riaz et al., 2014). Nevertheless, some studies showed very low correlations (e.g., Boyar et al., 2016; Clarke & Mahadi, 2017; Kossek et al., 2001; Law et al., 2008); some showed no relationship (Athota et al., 2020; Donaldson & Blanchard, 1995; Sargent & Terry, 1998; Staw & Barsade, 1993; Walker, 2013; Youssef & Luthans, 2007), and other studies found a negative correlation between SWB and job performance (e.g., Moradi et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2012). Overall, the findings revealed considerable variability. Three meta-analyses summarized the relationship of the cognitive and affective components of SWB with job performance (Erdogan et al., 2012; Ford et al., 2011; Shockley et al., 2012). These meta-analyses consisted of a small number of primary studies conducted in the USA, many of them using small-size samples (Walsh et al., 2018). This last fact means that second-order sampling error can happen as in Ford et al. (2011), where the variance explained by artifacts is greater than 100% in the case of LS and self-rated performance relationship. Shockley et al.’s (2012) meta-analysis reported credibility intervals that included zero for three out of four cases. This implies that the correlation found is not generalizable beyond the studies included in the meta-analysis. Finally, the meta-analysis of Erdogan et al. (2012) did not correct the observed correlations for the effect of artifactual errors (e.g., reliability in LS and job performance and sampling error), which produced an underestimation of the true relationship and the overestimation of true variance. The literature reviews of Lyubomirsky and her colleagues (Boehm & Lyubomirsky, 2008; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Walsh et al., 2018) mentioned two limitations of past meta-analyses: (a) many of the primary studies included in those meta-analyses date back many years and many used small-sample sizes and (b) they can suffer to some extent from publication bias (i.e., it is possible that a number of nonsignificant, unpublished studies were not included and only studies conducted in the USA were included). Together with those limitations, there are two additional ones that can be mentioned: (a) previous meta-analyses did not examine the relationship between job performance and the cognitive and affective components of SWB simultaneously, and (b) apart from Ford et al. (2011), previous meta-analyses did not distinguish between self-rated job performance and supervisory-rated job performance. This last distinction is relevant, as supervisory ratings of job performance are the main criteria in personnel decisions (Campbell & Wiernik, 2015; Salgado & Moscoso, 1996, 2019a, 2019b; Salgado et al., 2016). Research on the relationship between SWB and job performance has also been characterized by using a variety of estimates of SWB. Some studies have evaluated a global estimate of SWB, other studies have evaluated affective SWB or cognitive SWB only, and other studies have evaluated both SWB components. For instance, the series of studies by Wright and his colleagues (e.g., Wright & Cropanzano, 2000; Wright et al., 2007) used a measure of affective SWB, Law et al. (2008) evaluated cognitive SWB only, Zelenski et al. (2008) evaluated cognitive SWB and affective SWB but not overall SWB, and Salgado et al. (2019) evaluated cognitive SWB, affective SWB, and overall SWB. The variability in SWB-job performance correlations together with the fact that the studies assessed different SWB facets and components suggest that the relationship between overall SWB, its components, and job performance might be different from the relationships of job performance and cognitive and affective SWB. Moderator Effect of Self-rating vs. Supervisory Rating of Job Performance Almost all the studies in our database (with few exceptions) used one of these two types of ratings: (a) supervisory ratings of job performance or (b) self-ratings of job performance. Self-ratings were used in 69% of studies on cognitive SWB-job performance, in 33% of studies on affective SWB-job performance, and in 53.8% of the studies on overall SWB-job performance. In other research areas, for example, cognitive abilities and personality, studies using self-ratings of job performance typically found greater validity in comparison with the studies using supervisory ratings (Salgado & Moscoso, 2000). However, this moderator effect had not been meta-analytically examined in the SWB-job performance domain. In addition, interrater reliability of supervisory ratings is typically lower than .70, while self-ratings’ reliability is typically higher than .80 (Salgado & Moscoso, 1996, 2019a; Viswesvaran et al., 1996). As the reliability of the measures is a factor that attenuates the correlation between SWB and job performance, one can expect that the magnitude of the correlation be larger for the studies in which job performance was assessed with self-reports. Also, it must be pointed out that the correlation between self-ratings of job performance and SWB measures might also be larger because of common-method variance, particularly when cross-sectional studies are carried out. For these reasons, an examination of the potential moderator effects of the rating type seems to be in order. Consequently, we state the following research question. Research Question 1: Does the type of job performance ratings (supervisory ratings vs. self-ratings) moderate the validity of SWB and its components as predictors of job performance? Suppressor Relationship in the Prediction of Job Performance by a Composite of Cognitive and Affective SWB Most of the primary studies conducted so far, and meta-analyses mentioned above examined the relationship of one of SWB components with job performance, but the joint relationship of both SWB components with job performance has been scarcely researched in primary studies, and it was not meta-analytically tested. Some recent primary research used a global measure of SWB that included both cognitive and affective measures (Jalali & Heidari, 2016; Jones, 2006; Merriman, 2016; Rabenu et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2015). However, they did not test the specific contribution of each SWB component in the prediction of job performance. Recently, Salgado et al. (2019) examined this issue, both concurrently and predictively. More specifically, Salgado et al. tested the predictive efficiency of cognitive SWB, affective SWB, a global measure of SWB, and a composite of cognitive plus affective SWB measures. They found that the global measure of SWB showed similar validity to the two components considered separately. Interestingly, a noteworthy finding was that the composite of cognitive and affective SWB showed a much larger validity than the other three alternative measures (i.e., cognitive SWB, affective SWB, and global SWB). However, the most significant finding was that the cognitive and the affective components of SWB showed a suppressor relationship with job performance. In other words, the magnitude of the effect of the affective component increased when the cognitive component entered in the regression equation. This suppressor effect of the two SWB components in their relationship with job performance had not previously been found in the research literature. Salgado et al. (2019) explained this effect theoretically suggesting that the cognitive component of SWB (i.e., satisfaction with life) would function as an emotion regulation mechanism. It would operate “suppressing” (avoiding or reducing) negative emotions, which, subsequently, would produce greater frequency of positive emotions, and, therefore, affective SWB would have a greater effect on job performance. Salgado et al. also suggested that because cognitive SWB is typically more stable over time than affective SWB, the cognitive component of SWB would also have the effect of reinforcing the stability of affective SWB, which would subsequently make the effect of affective SWB on job performance stronger (because of the smaller variability and the smaller measurement error) over time. Suppressor effects are not unknown in the SWB literature and several suppressor effects related to well-being have been described previously. For instance, Watson et al. (2013) found a suppressor effect between euphoria and well-being for predicting psychological-health problems (e.g., depression, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and panic). In another study, Paulhus et al. (2004) found that two emotions, guilt and shame, maintained a suppressing relationship for predicting depression. To the best of our knowledge, this suppressor effect of cognitive SWB and affective SWB with job performance has not been re-examined or replicated yet. Moreover, it must be taken into account that the study of Salgado et al. (2019) used supervisory ratings to evaluate job performance. Therefore, it remains unexamined whether the suppressor effect also exists when job performance is self-rated. A comprehensive meta-analysis that calculates the specific correlation (effect size) of each SWB component with job performance would allow for the testing of the hypothesis of the suppressor relationship of cognitive and affective SWB with job performance. Based on the previous rationale, we posit the following two research questions: Research Question 2: What is the magnitude of the joint relationship of cognitive SWB and affective SWB with supervisory job performance and self-reported job performance? Research Question 3: Do cognitive SWB and affective SWB show a suppressor relationship for predicting supervisory job performance and self-rating job performance? Main Objectives In summary, despite the fact that research showed that SWB consists of a cognitive component and an affective component, some empirical studies evaluated one of the components, but not both, and other studies used an overall measure of SWB that did not permit the estimation of the specific contribution of each component to the prediction of job performance (Diener et al., 2003; Fisher, 2010). Another issue unexamined in previous research is whether affective SWB shows incremental validity over cognitive SWB for predicting job performance. This study has two main goals: (1) to examine the moderator effects of the performance measure (self-report vs. supervisory ratings) and (2) to test the hypothesis of the suppressor effect of cognitive SWB on affective SWB to predict job performance. In order to achieve these goals, we conducted a series of psychometric meta-analyses. Literature Search Using three strategies, we searched for studies that reported correlations or data which permit to calculate the correlation between a measure of SWB (i.e., overall SWB, PA, NA, EB, LS, and the like) and a measure of job performance. The first strategy was to conduct electronic searches using the following databases and meta-databases: PsycLit, Google, Scholar-Google, ERIC, Elsevier, Sage, Wiley, Academy of Management, Springer, and EBSCO. We used the following keywords: “subjective well-being,” “psychological well-being,” “satisfaction with life,” “happiness,” “positive affect,” “negative affect,” “emotional balance,” “SPANE,” in combination with “job performance,” “performance ratings,” and “work performance.” The second strategy was to examine the section of references of the meta-analyses and narrative reviews mentioned above, and the references of collected documents to identify potential papers not included in the previous set. The third strategy was to contact international researchers to obtain previously unidentified papers. The final database consisted of 34 independent samples using supervisory performance ratings and 38 independent samples using self-reported job performance. The list of studies and their data appear in the Appendix. The Bioethics Committee of our university declared the meta-analyses carried out with published and unpublished studies exempt from approval because they do not include personal identification data. Inclusion Criteria and Decision Rules As the primary purpose of this meta-analysis was to determine the correlation between SWB and its components with real job performance, in the final database we included only documents reporting correlational studies with real incumbents. In other words, we did not consider laboratory experiments, studies with no real people, and studies with student samples. We also excluded studies reporting validity estimates for physical symptoms and clinical scales. When studies reported a range of numbers of incumbents, we coded the smallest number to provide a more conservative estimate. When an article or document reported data from two or more independent samples of participants, they were entered into the meta-analysis as separate correlations. When a study reported correlations for the same sample obtained in different occasions, the average estimate served as the data source for that sample. Finally, when a study used two performance measures for the same sample at the same time, the average correlation was entered as data source. We also excluded 11 studies because the same coefficients had been reported in another paper included in the dataset. The inclusion criteria fulfill the criteria and recommendations of the Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS) specified in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (2019; available at https://apastyle.apa.org/manual/related/JARS-MARS.pdf) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA). Table 1 Results of the Meta-analysis for the Combinations of SWB and Supervisory Job Performance Ratings   Note. SWB = subjective well-being; k = number of independent samples; N = total sample size; rw= mean observed validity; S2r = sample size weighted observed variance of the correlations; SDr = standard deviation of observed validity; ρop = operational validity; ρt = true correlation (validity corrected for criterion and predictor reliability); SDρ = standard deviation of ρ; %VE = percentage of variance accounted for by artifactual errors; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the true correlation; 90% CV = 90% credibility value based on the true correlation. Agreement between Coders The authors coded all correlation coefficients independently and the following categories of data points were compared: (1) sample size, (2) correlation coefficient, (3) performance measure (self-ratings vs. supervisor ratings), (3) performance appraisal purpose (i.e., administrative vs. research), (4) SWB measure, (5) SWB reliability, and (6) performance reliability. The initial agreement was 95.3%. The authors examined the disagreements by referring back to the studies and discussing until they reached consensus. Publication Bias and Identification of Outliers We used three methods to detect potential publication bias: (1) comparison of the average observed correlation of published and unpublished studies, (2) correlation between sample size and effect size, and (3) cumulative meta-analyses (CMA). The total of published and unpublished studies, on average, showed practically the same effect size. Therefore, we can reject the idea that the publication source distorts average validity. The correlation between sample size and effect size was small and statistically non-significant; therefore, we can also reject this source of publication bias. Concerning to CMA, there is agreement that CMA is the most robust technique for detecting publication bias (Borenstein, 2005; Kepes et al., 2012; Schmidt & Hunter, 2015; Schmidt & Le, 2014). CMA results showed no evidence of publication bias. Therefore, the three techniques agreed that publication bias was not a relevant issue in the current case. In this meta-analysis, we used the Sample Adjusted Meta-Analytic Deviance Statistic (SAMD) by Huffcutt and Arthur (1995; see also Beal et al., 2002) and the number of SD units below or above the mean of the distribution of correlations (Wilcox, 2014) to identify potential outliers. The two outlier criteria agreed as they identified two studies, with four validity coefficients, as potential outliers. They were the study of Moradi et al. (2014) and the study of Singh et al. (2012). The corresponding SAMD statistics were remarkably larger than 1.96 (p < .001). All SD units below the mean were larger than 3 SD units (i.e., p < .001). Therefore, the studies of Moradi et al. (2014) and Singh et al. (2012) were considered outliers in this study, and meta-analyses were done with and without these two studies. The effects of these two outliers were substantial on the observed variance, adding artifactual variance. SWB Reliability SWB reliability and its cognitive and affective components were estimated using the coefficients (internal consistency) reported in individual studies. Some of the studies did not provide reliability coefficients of the instruments, and, in those cases, we used the mean value of the reliability distribution of all combined studies as the study reliability. Next, we developed an empirical distribution for overall SWB and each SWB component. Mean reliabilities were .83 (SD = .08) for cognitive SWB, .80 (SD = .08) for affective SWB, and .85 (SD = .10) for overall SWB. The meta-analysis of Busseri (2018) reported reliabilities of .86 (SD = .07), .81 (SD = .07), and .82 (SD = .04) for positive affect, negative affect, and satisfaction with life, respectively, which are very similar to reliabilities found in this meta-analysis. Job Performance Reliability In the studies included in the dataset, job performance was assessed with self-reports and/or supervisory ratings. Therefore, two different estimates of reliability are required. In the case of self-reports, an internal consistency coefficient (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) is the estimate of choice in the absence of a coefficient of equivalence and stability (CES) (Schmidt et al., 2003). In the case of supervisor ratings, in the absence of a CES, an interrater coefficient is the appropriate one (Salgado & Moscoso, 1996, 2019a; Viswesvaran et al. 1996). As some studies did not provide job performance’s reliability, we developed an empirical distribution of internal consistency coefficients for self-reports of job performance. In the case of supervisor ratings, we developed an empirical distribution considering the nature of supervisor ratings. Salgado and Moscoso (2019a) found that the purpose of performance appraisal (research vs. administrative) is a powerful moderator of interrater reliability. As only one study in our dataset reported interrater reliability, we used the distributions developed by Salgado and Moscoso (2019a) according to the following rules: (1) if supervisor ratings were collected for research purposes, we used .61 (SD = .11) as an estimate of interrater reliability; (2) if supervisor ratings were collected for administrative purposes, we used an estimate of .48 as interrater reliability. If the job performance measure was a self-report, and the study did not provide the coefficient, we used the mean value of the distribution as reliability (.80). Average reliability was .80 (SD = .09) for self-reported job performance and .61 (SD = .11) for supervisory job performance ratings. Meta-analyses by SWB-Job Performance Source These meta-analyses were conducted to respond to the Research Question 1, concerning potential moderator effects of source of job performance ratings on the relationship between SWB and job performance. These meta-analyses allow us to compare true score correlation for studies which used self-reports of job performance and with the true score correlation obtained for studies which used supervisory ratings. Tables 1 and 2 show the results of these meta-analyses. Table 2 Results of the Meta-analysis for the Combinations of SWB and Self-reported Job Performance Ratings   Note. SWB = subjective well-being; k = number of independent samples; N = total sample size; rw= mean observed validity; S2r = sample size weighted observed variance of the correlations; SDr = standard deviation of observed validity; ρop = operational validity; ρt = true score correlation (validity corrected for criterion and predictor reliability); SDρ = standard deviation of ρ; %VE = percentage of variance accounted for by artifactual errors; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the true correlation; 90% CV = 90% credibility value based on the true correlation. The results show that the source of job performance ratings operates differently for the various SWB components and measures. More specifically, true correlation is noticeably larger for self-reported job performance than for supervisory ratings in the case of cognitive SWB (ρt = .30 vs. ρt = .17), but the true score correlation is considerably larger for supervisory ratings in affective SWB (ρt = .49 vs. ρt = .30), slightly larger in overall SWB (ρt = .42 vs. ρt = .40), and in SWB estimate when all studies were combined (ρt = .35 vs. ρt = .33). On average, true score correlation is slightly larger (ρt = .35 vs. ρt = .33) for the supervisory ratings of job performance. Table 3 Correlation Matrices for the Relationships between Cognitive SWB, Affective SWB, and Job Performance   Considering all the results, Research Question 1 does not have a single answer. The results indicate that the source of job performance ratings is a relevant moderator of the relationship between SWB and job performance, but it operates differently for cognitive SWB and affective SWB. For cognitive SWB, the relationship is larger when job performance is assessed with self-reports, while for affective SWB and overall SWB, the relationship is larger when supervisors are the source of job performance ratings. As far as observed variability was concerned, artifactual errors explained more variance for studies using supervisory ratings than for studies using job performance self-reports. Ninety percent CVs were all positive and very different from zero, which indicates that relationships between SWB and job performance generalize for both self-reports and supervisory ratings. Examination of Suppressor Relationship in the Prediction of Job Performance by a Compound of Cognitive and Affective SWB In order to establish the joint capacity of cognitive and affective SWB to predict job performance and to know whether cognitive SWB shows a suppressor effect on affective SWB, we conducted a series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses using the validity estimates found in previous meta-analyses. Multiple regressions were conducted in two steps. In the first step, affective SWB was the predictor, as it showed a larger correlation with job performance. In the second step, both affective and cognitive SWB were entered into the equation. Multiple regression requires knowing the correlation between cognitive SWB and affective SWB, but the studies included in the database rarely reported this information. For this reason, we used the values found in the meta-analyses of Busseri (2018) as the best estimate of the correlation between cognitive SWB and affective SWB. Finally, we created three matrices of correlations reported in Table 3, using cognitive SWB and affective SWB and three correlation estimates of job performance. We carried out three hierarchical multiple regression analyses. Table 4 reports the results of these analyses. The first one used the correlations of cognitive and affective SWB with job performance, without distinguishing if job performance was assessed by supervisory ratings or self-reports. In this case, R was .374, and cognitive SWB added practically no explained variance over affective SWB (13.7% vs. 14.0%), but beta weights were significant for the two SWB components. In this case, the compound of cognitive and affective SWB showed a multiple correlation similar to the correlation found for overall SWB in the prediction of both self and supervisory ratings of job performance, as it was reported in Tables 1 and 2. Table 4 Results of the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses to Predict Job Performance, Self-reported Performance, and Supervisory Performance Ratings   Note. R = multiple correlation; R2 = square multiple correlation; Δ = incremented explained variance. Self-reported job performance was the dependent variable, and cognitive SWB and affective SWB were the independent variables in the second multiple regression analysis. In this case, cognitive SWB showed incremental validity over affective SWB. Multiple correlation R was .334, which is higher than the two bivariate correlations (.30 and .30, respectively). The increment of explained variance was 2.2%, and beta values were significant. Betas were similar for cognitive and affective SWB, although slightly higher for affective SWB (.202 vs. .177). Therefore, the two components of SWB added validity for predicting self-reported job performance. However, the magnitude of the multiple correlation of the compound is smaller than the bivariate correlation of overall SWB with self-reported job performance (.334 vs. .40, respectively). In the third multiple regression analysis, the dependent variable was supervisory performance rating, and cognitive and affective SWB were the independent variables. In this case, R is larger than the true correlation of affective SWB and supervisory ratings of job performance (.516 vs. .49). Therefore, the addition of cognitive SWB to the equation increased predictive validity, and also increased explained variance by 2.6%. However, beta for affective SWB increased by 26% (.615 vs. .49), while beta for cognitive SWB was negative (-.205); nonetheless, its zero-order correlation was positive (ρ = .17). These two beta values indicate that cognitive SWB acted as a suppressor variable for predicting supervisory ratings of job performance. Suppressor effect suggests that the presence of this variable in a regression equation increases the predictive power of an independent variable on the dependent variable. More specifically, we found a net or cross-over suppression. Salgado et al. (2019) also found this cross-over suppression effect of cognitive SWB in their longitudinal study. The net or cross-over suppression refers to cases in which two independent variables and a dependent variable correlate positively with each other, but the inclusion of the two independent variables in regression equations increases beta of the most influential variable and changes beta sign of the weakest variable; that is, positive zero-correlation becomes a negative beta (Cohen & Cohen, 1975; MacKinnon et al., 2002; Paulhus et al., 2004; Salgado et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2013). In order to test if the increment of affective SWB beta is significant, we computed Sobel test, z test, and 95% confidence interval (Sobel, 1982; MacKinnon, 2008; MacKinnon, Lockwood, et al., 2007). For the Sobel test, we used a calculator developed by Preacher and Leonardelli, which is available online at http://www.quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm. We also computed 95% confidence interval for the suppressor effect using the distribution of the product of two regression coefficients (z test). In this case, we used the PRODCLIN program developed by MacKinnon, Fritz, et al. (2007). Sobel test was -9.97 (p < .001), z test was -.12 (p < .01), and upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval were -.146 and -.105. Therefore, the three criteria showed that the suppressor effect was significant. The finding that cognitive SWB suppresses some affective SWB variance in the case of supervisory ratings of job performance agrees with previous finding of Salgado et al. (2019). Also, it supports Diener’s suggestion that both components of SWB should be assessed and measured independently. This suppressor relationship has both theoretical and practical implications that we will discuss later. In summary, findings also revealed that the source of job performance ratings (i.e., self-reported vs. supervisory ratings) moderates the relationship of SWB and its components with job performance. Also, we found that there was a cross-over suppression relationship between affective and cognitive SWB in the prediction of supervisory ratings of job performance. This meta-analysis examined the current empirical evidence on the relationship between job performance and SWB, using Diener’s two-component model of SWB to categorize the studies conducted in the last three decades. The findings based on primary studies showed an enormous variability in the estimates of the SWB-performance relationship, with some studies reporting negative correlations, several reporting no relationships, and other studies reporting correlations of small-to-medium size. Previous meta-analyses by Erdogan et al. (2012), Ford et al. (2011), and Shockley et al. (2012) estimated the average correlation of SWB cognitive and affective components with job performance, but it remained untested (a) whether the two components of SWB showed similar correlation with job performance; (b) whether despite the variability reported, there was evidence of generalizability in the relationships; (c) whether the correlation had been influenced by the source of job performance ratings (i.e., self-report vs. supervisory ratings); (d) whether a compound of cognitive and affective SWB measures shows higher explained variance than an overall measure of SWB or the variance explained by the respective SWB components taken separately, and (e) whether they were affected by publication bias. In examining the empirical evidence with meta-analytic techniques, the present research made several unique contributions to the clarification of the relationships between SWB and its two components with overall job performance and aimed to answer three research questions. The first unique contribution has been to show that SWB and job performance are moderately correlated, regardless of whether SWB is evaluated as overall, cognitive, or affective SWB. This correlation means that the higher the SWB level, the higher the job performance level. Therefore, overall SWB and its two components are valid predictors of performance ratings at work. The correlation is similar or even higher than the correlation found for other well-known variables related to job performance, such as the Big Five personality dimensions, cognitive abilities, emotional intelligence, the situational judgment test, interviews, and in-basket tests (see, for instance, Aguado et al. 2019; Alonso et al., 2015; Alonso et al., 2017; Herde et al., 2019; García-Izquierdo et al., 2012; García-Izquierdo et al., 2020; Joseph & Newman, 2010; Judge et al., 2013; Morillo et al., 2019; Moscoso et al., 2012; Moscoso & Salgado, 2001; Ones et al., 1993; Otero et al., 2020; Ryan & Derous, 2019; Salgado et al. (2015), Salgado, 2017; Salgado & Lado, 2018; Salgado & Moscoso, 2019b; Salgado & Tauriz, 2014; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, 2004; Whetzel et al., 2014). Moreover, as evidenced by 90% credibility values, overall SWB, cognitive SWB, and affective SWB generalize validity across samples, instruments, occupations, organizations, and countries. The second contribution has been to demonstrate that affective SWB is a much more valid predictor of job performance than cognitive SWB. Affective SWB also showed higher validity than overall SWB. This finding suggests that emotions at work are a very critical characteristic of individual differences in predicting job performance. The third unique contribution has been to determine the moderating role of the source of job performance measures. Our findings showed that the validity of SWB is very similar for supervisor ratings and self-ratings of job performance (.33 vs. .35), although the validity is, on average, 6.1% larger for supervisor ratings. This finding is important because it had been believed that the validity for predicting self-ratings was typically higher due to common-method variance, among other factors. The findings of this meta-analysis, therefore, indicate that job performance self-ratings are acceptable estimates of job performance in the case of SWB, that they do not inflate the magnitude of validity, and that they can be a substitute for supervisory job performance ratings in this psychological domain. The fourth unique contribution has been to demonstrate that the predictive capacity of a compound of cognitive and affective SWB depends powerfully on how job performance has been assessed. If we do not consider the source of job performance ratings, then a compound of cognitive and affective SWB shows similar validity to a measure of overall SWB. Therefore, both alternative SWB estimates are similarly useful. Nevertheless, our findings showed that the contribution of cognitive SWB to predicting job performance, in the presence of affective SWB, is different when one takes into account the source of job performance ratings. In the case of self-reported job performance, cognitive SWB added explained variance to the variance accounted for by affective SWB. Moreover, the effects of cognitive and affective SWB are very similar, given the respective beta weights. However, this finding does not hold when job performance is assessed with supervisory ratings. Interestingly, in this last case, the relationship with cognitive and affective well-being showed a suppressor cross-over relationship, as beta for affective SWB increased, and beta for cognitive SWB became negative. This suppressor relationship had been found in a primary study by Salgado et al. (2019). This meta-analysis also has implications for the theory and practice of psychology at work. The present meta-analytic findings provide empirical support for the Happy-Productive-Worker Hypothesis (HPWH), as both components of SWB correlated with job performance. Findings indicate that employees scoring higher on cognitive SWB (i.e., life satisfaction) and affective SWB also showed a higher level of job performance. As cognitive SWB has been termed life satisfaction or happiness on many occasions, so, by extension, we can conclude that the happier the employees, the better their job performance. Another potential implication for the theory is about the relationship between SWB’s cognitive and affective components. Many primary studies and a meta-analysis (e.g., Busseri, 2018) showed that the two components are highly related. However, potential cross-over effects between cognitive and affective components have been overlooked. Based on the findings of this research, it can be speculated that cognitive SWB may be a valid predictor of job performance due to its strong relationship with affective SWB. For instance, people that tend to experience more positive emotions might “generate” a higher level of satisfaction with life, and people that tend to experience more negative emotions might “generate” a lower level of satisfaction with life. In this conjecture, emotions will function as a trigger for satisfaction with life. This meta-analysis cannot clarify this hypothesis, and future studies should test it. A third implication for the theory has been to show that feelings can play a critical role in employees’ job performance. Salgado et al. (2019) suggested a theoretical explanation for the cross-over suppression situation finding, according to which cognitive SWB would function as an emotional regulation mechanism. As affective SWB is a balance of positive and negative emotions, cognitive SWB would act “suppressing” (avoiding) negative emotions, which, subsequently, would produce a higher frequency of positive emotions. Thus, affective SWB would have a more substantial effect on job performance. Moreover, as cognitive SWB is more stable over time than affective SWB, the former would reinforce or improve the stability of the effect of affective SWB on job performance over time. The comparison of the validity of overall SWB (R = .42) with the validity of affective SWB plus cognitive SWB (R = .516) for predicting supervisory ratings of job performance highlights the importance of taking into account suppressor effects when the construct validity of SWB components is examined. From a personnel selection perspective, as the findings showed that overall SWB predicts similarly well self-report and supervisory ratings of job performance, and this is not true for cognitive and affective SWB, an estimate of overall SWB could be the best choice when both informative sources of job performance are simultaneously used (e.g., when multi-source feedback is collected). However, if supervisory ratings of job performance are the criterion to be predicted, the best option is to supplement a measure of affective SWB with a measure of cognitive SWB. Another practical strategy to increase employees' job performance is to develop workplace settings that activate and reinforce employees' positive emotions. Two potential ways of increasing affective SWB are (a) increasing the frequency of positive feedback and controlling the frequency of negative feedback and (b) increasing positive feedback and reducing negative emotions by lowering negative feedback, and implanting stress at work-reducing programs (Rahm et al., 2017). Recently, Heintzelman et al. (2020) developed an intervention program to increase SWB that can be applied both in in-person and online formats. A randomized controlled trial showed the efficacy of the program in increasing SWB. This kind of program, particularly in the on-line format, may be promising as a tool for improving SWB in the workplace. As with all studies, the current one also has some limitations. This meta-analysis examined the relationship of SWB and its components with overall job performance. However, as job performance is a multi-dimensional construct (Campbell & Wiernik, 2015; Harari et al., 2016; Hoffman et al., 2007; Salgado & Moscoso, 2019a), the current estimates cannot be generalized to other job performance dimensions (e.g., citizenship performance, counterproductive behaviors at work, and innovative performance). This is the first limitation of this study. For example, we found no studies examining the relationship between SWB and its components with innovative performance, two studies for the combination SWB-task performance, three for the combination cognitive SWB-citizenship performance, and four studies for the combinations affective SWB-task performance and affective SWB-citizenship performance. Also, we were not able to find studies on the relationships between SWB and its components and non-rating measures of performance. This would be the second limitation of this meta-analysis. Future studies should examine the validity of SWB measures as predictors of other measures of job performance (e.g., production records, work sample tests, simulations, and other performance dimensions, such as task, citizenship, innovation, counterproductivity). Similarly, current validity estimates cannot be generalized to other relevant organizational criteria, such as turnover and absenteeism. Future studies should also be devoted to determining the validity of SWB measures to predict organizational criteria. A fourth limitation is that current findings do not permit us to assess the causal direction of the SWB relationship. Although longitudinal studies, on average, point out that the level of SWB at Time 1 correlates with the level of job performance at Time 2, in other words, that in those studies SWB precedes job performance, the nature of designs does not allow us to establish if previous job performance determined the level of SWB at Time 1 or if the SWB-job performance relationship is due to the effect of a third variable correlated with SWB, with job performance, or with both (Boehm & Lyubomirsky, 2008; Walsh et al., 2018). A fifth limitation of this meta-analysis refers to whether the relationship between cognitive SWB and affective SWB remains stable or declines over time, as it was found in previous research (e.g., Cropanzano & Wright, 1999, 2001; Salgado et al., 2019). The studies included in the database do not contain information to examine this issue. In summary, this study contributes to the clarification of the relationships between SWB and job performance. It demonstrates that there is a substantial relationship between these two variables. Using Diener’s two-component model of SWB, findings show that affective SWB correlates stronger with job performance than cognitive SWB and that there is a cross-over suppression relationship between cognitive and affective SWB for predicting supervisory ratings of job performance. Also, the study clarifies that the source of performance ratings moderates the relationship. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgments Dr. A. Berges (U. Zaragoza) and Dr. M. Iglesias (Magna Gestio) served as action editors for this manuscript. We wish to acknowledge Dr. Berges and Dr. Iglesias and three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions on earlier versions of the current article. Cite this article as: Moscoso, S. & Salgado, J. F. (2021). Meta-analytic examination of a suppressor effect on subjective well-being and job performance relationship. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 119-131.https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a13 Funding: This research was partially supported by grant PSI2017-87603-P from the Spanish Ministry of Education to Silvia Moscoso and Jesús F. Salgado. References |

Cite this article as: Moscoso, S. & Salgado, J. F. (2021). Meta-analytic Examination of a Suppressor Effect on Subjective Well-Being and Job Performance Relationship. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 119 - 131. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a13

silvia.moscoso@usc.es Correspondence: silvia.moscoso@usc.es (S. Moscoso).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS